Palinopsia

X-ray film images, 2020

The body was the first site of conquest in the desire to make the invisible visible. X-rays cut through the inner surfaces, turning flesh into a photographic medium that light can penetrate. The dropping of the first atomic bomb was the largest photographic event ever to occur. Inscribed by catastrophic light, Hiroshima and Nagasaki became cameras. Atomic shadow traces appeared throughout the cities—body-shaped black marks where people stood at the time of the detonation. The violent light bleached the buildings and sidewalks except where a body had interrupted it. The shadows were photograms.

Atomic veterans who had watched the tests in Nevada’s desert recalled turning away from the bomb’s blinding light and covering their eyes with their arms. The flash—an X-ray—rendered their bodies momentarily transparent. They saw through their eyelids, and the bones in their arms became visible. Akira Lippit writes:

“The lethal force of X-rays is recapitulated by the atomic radiation, which echoes the capacity of catastrophic light to penetrate the body and erase the distinction between inside and out, body and environment, images of destruction and unimaginable destruction. X-rays and atomic radiation are lined in a secret narrative, bound by a logic that is historical, overdetermined, and destined—and, at the same time, incidental, accidental, and arbitrary.”

X-rays and gamma rays are known cancer-causing agents. The generation of atomic veterans and downwinders X-rayed by atomic weapons testing gave birth to the generation X-rayed by medical technology. For the future generations afflicted by genetic mutations, childhood cancer, or the fear of either, the connection between the technological and corporeal is used to reduce social tensions (for example, with X-rays, MRIs, or fetal ultrasound images). Simultaneously, it creates an interdependence that is only mitigable with the use of more technology. Radiation, like the nuclear industry, is involved in an interesting paradox: the seductive use of civilian nuclear power plants allows for the continued production of weapons-grade plutonium; the compounds used to cure cancer are also the ones that create it; and the effect of radiation, rendering the body’s interior visible, can also create illness that makes it taboo—secret. And that which is secret is socially invisible.

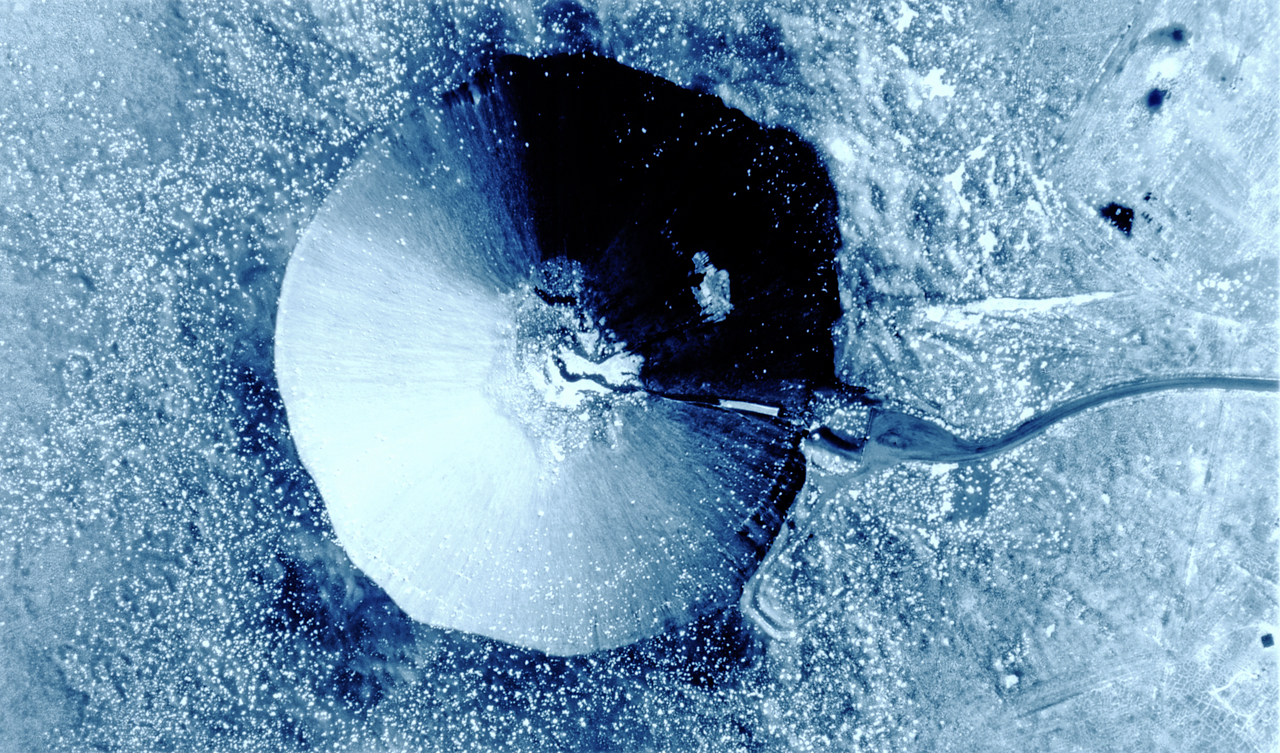

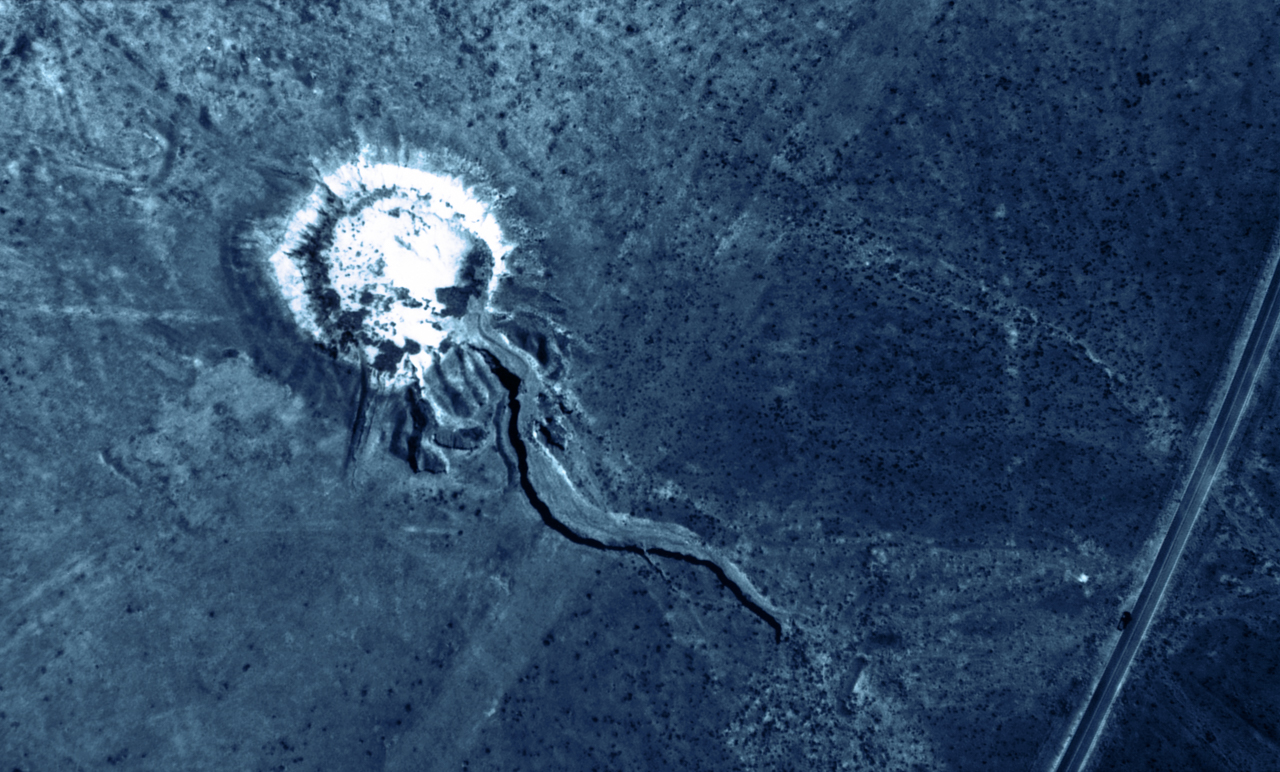

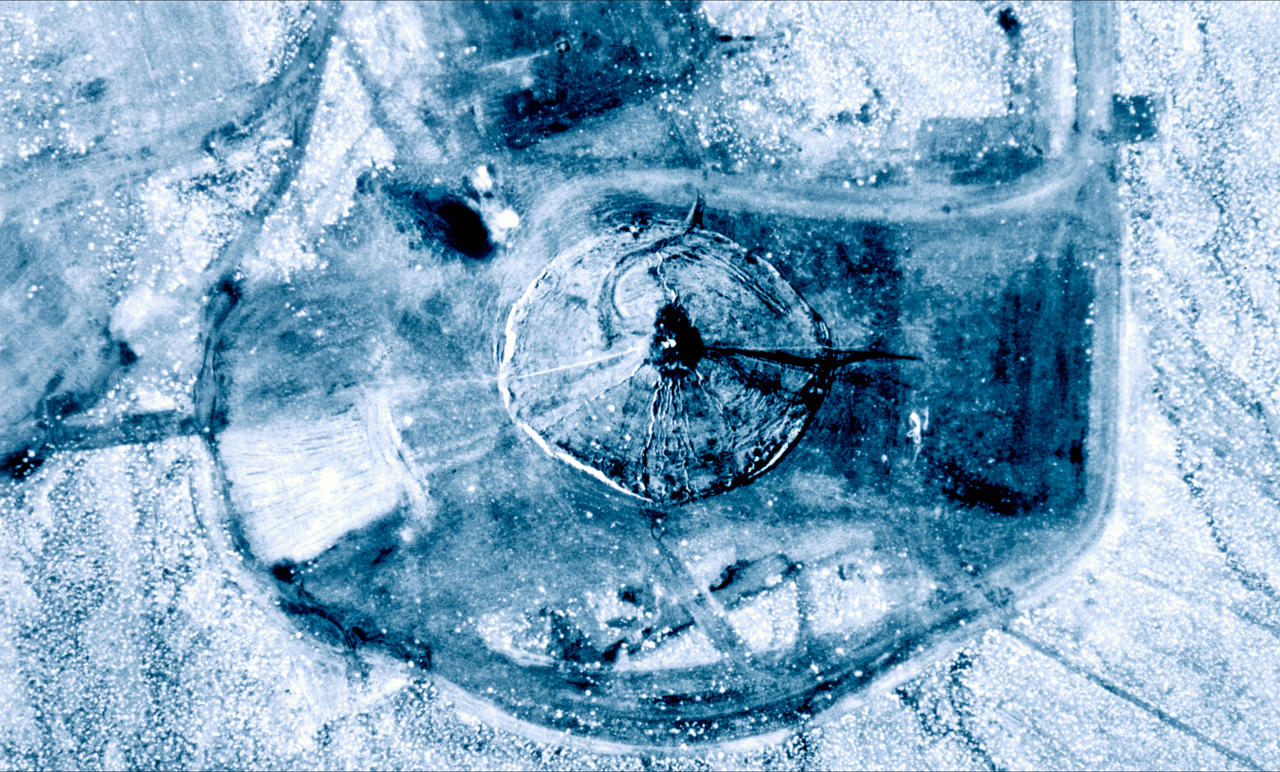

I created Palinopsia by photographing a computer screen displaying Google Earth satellite images of bomb craters at the Nevada Test Site. The film captures an inverse of the image, filling the absent cavity with visible light. It creates an illusion of matter where the matter was removed, reflecting radiation’s introduction into the atmosphere. My appropriation of these images is an act of counter-surveillance and provides commentary on image consumption and the inaccessibility of place and its history.

Palinopsia

X-ray film images, 2020

The body was the first site of conquest in the desire to make the invisible visible. X-rays cut through the inner surfaces, turning flesh into a photographic medium that light can penetrate. The dropping of the first atomic bomb was the largest photographic event ever to occur. Inscribed by catastrophic light, Hiroshima and Nagasaki became cameras. Atomic shadow traces appeared throughout the cities—body-shaped black marks where people stood at the time of the detonation. The violent light bleached the buildings and sidewalks except where a body had interrupted it. The shadows were photograms.

Atomic veterans who had watched the tests in Nevada’s desert recalled turning away from the bomb’s blinding light and covering their eyes with their arms. The flash—an X-ray—rendered their bodies momentarily transparent. They saw through their eyelids, and the bones in their arms became visible. Akira Lippit writes:

“The lethal force of X-rays is recapitulated by the atomic radiation, which echoes the capacity of catastrophic light to penetrate the body and erase the distinction between inside and out, body and environment, images of destruction and unimaginable destruction. X-rays and atomic radiation are lined in a secret narrative, bound by a logic that is historical, overdetermined, and destined—and, at the same time, incidental, accidental, and arbitrary.”

X-rays and gamma rays are known cancer-causing agents. The generation of atomic veterans and downwinders X-rayed by atomic weapons testing gave birth to the generation X-rayed by medical technology. For the future generations afflicted by genetic mutations, childhood cancer, or the fear of either, the connection between the technological and corporeal is used to reduce social tensions (for example, with X-rays, MRIs, or fetal ultrasound images). Simultaneously, it creates an interdependence that is only mitigable with the use of more technology. Radiation, like the nuclear industry, is involved in an interesting paradox: the seductive use of civilian nuclear power plants allows for the continued production of weapons-grade plutonium; the compounds used to cure cancer are also the ones that create it; and the effect of radiation, rendering the body’s interior visible, can also create illness that makes it taboo—secret. And that which is secret is socially invisible.

I created Palinopsia by photographing a computer screen displaying Google Earth satellite images of bomb craters at the Nevada Test Site. The film captures an inverse of the image, filling the absent cavity with visible light. It creates an illusion of matter where the matter was removed, reflecting radiation’s introduction into the atmosphere. My appropriation of these images is an act of counter-surveillance and provides commentary on image consumption and the inaccessibility of place and its history.