Big Pharma

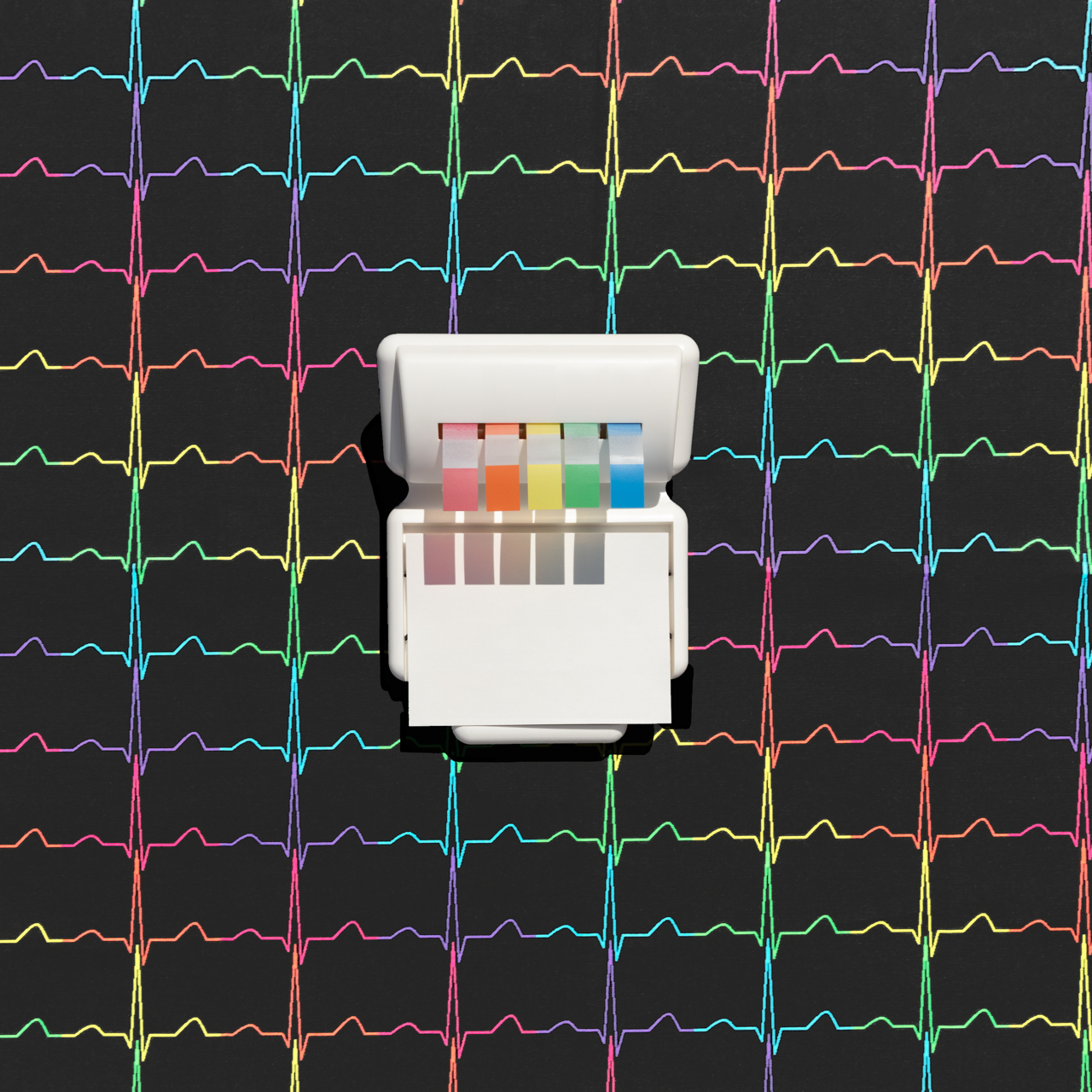

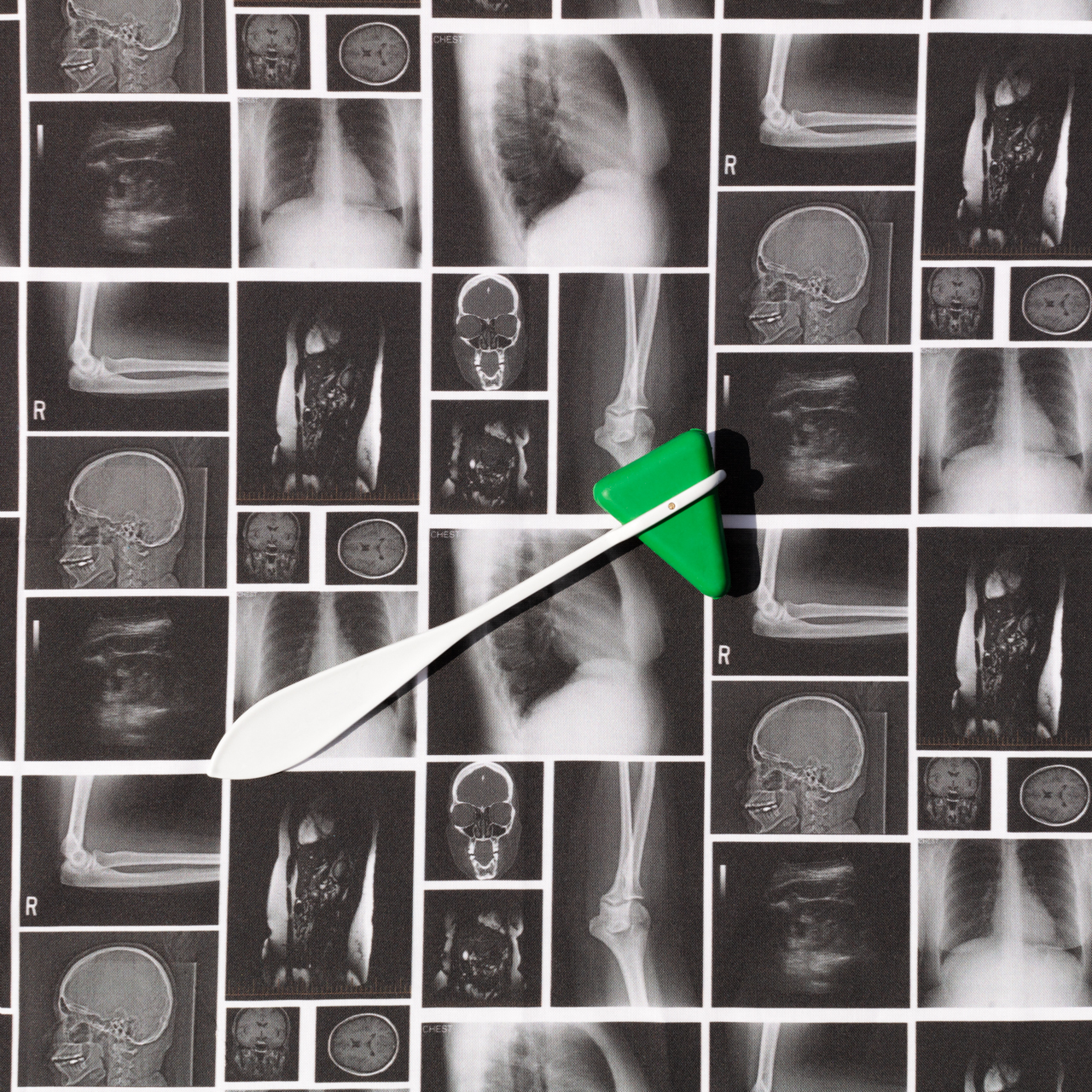

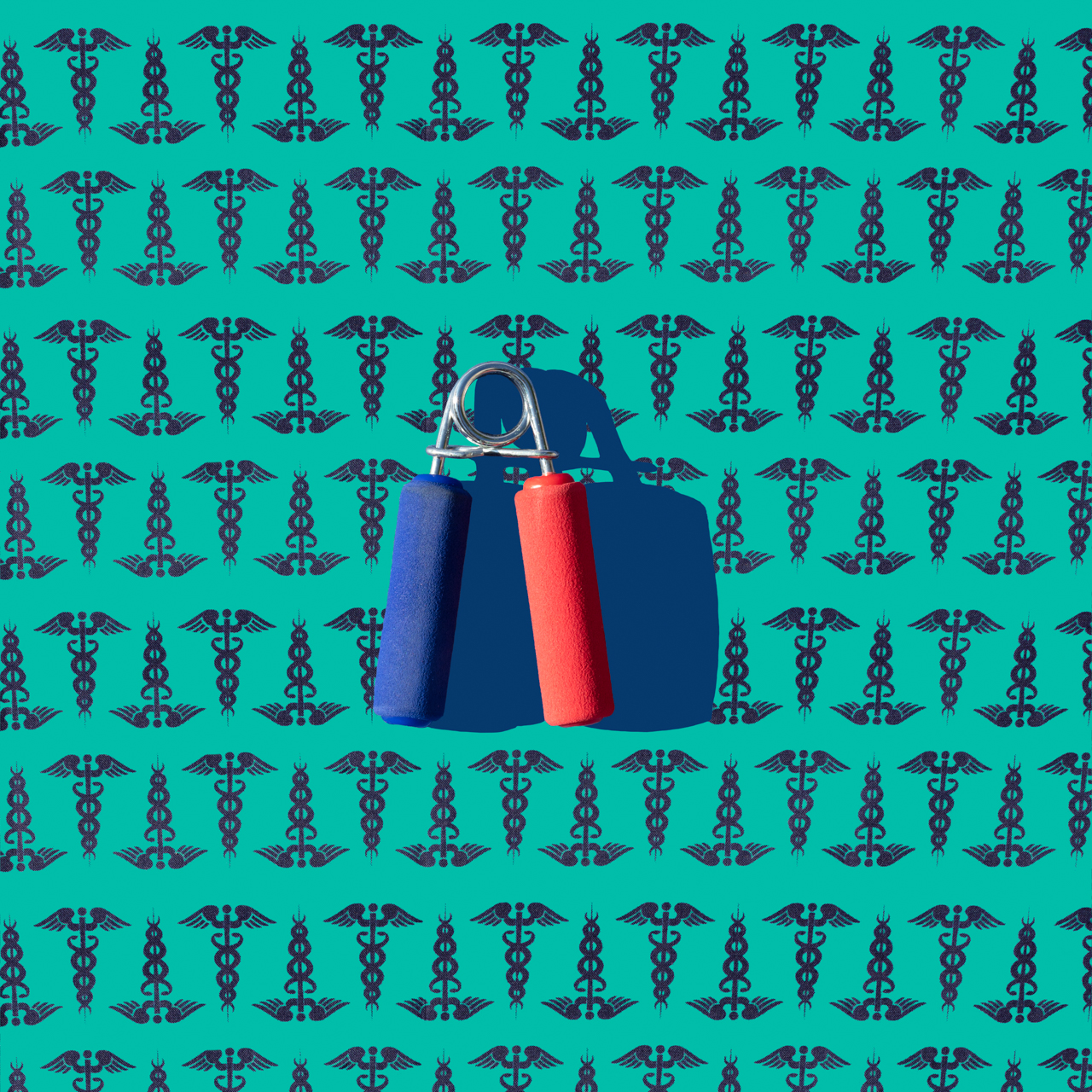

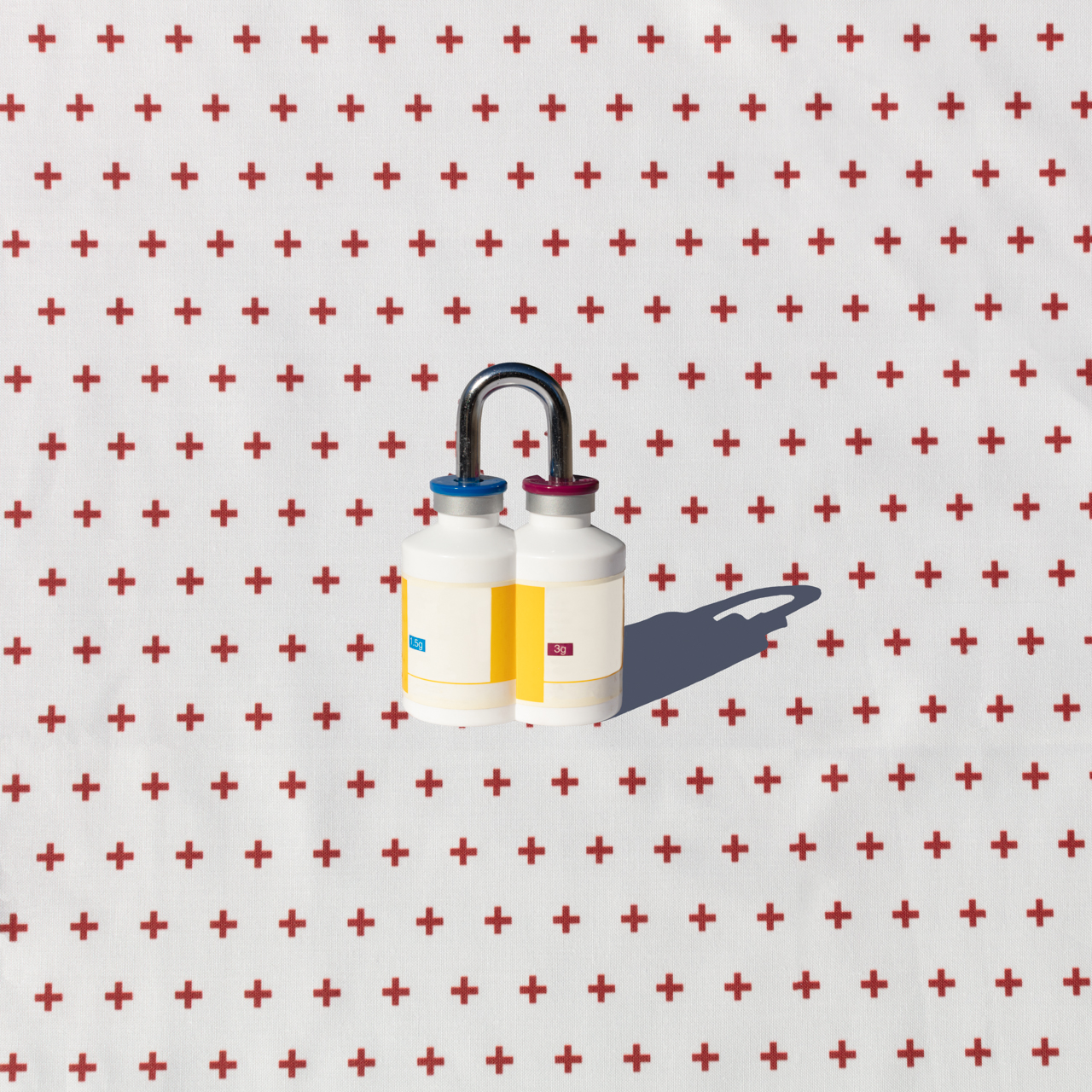

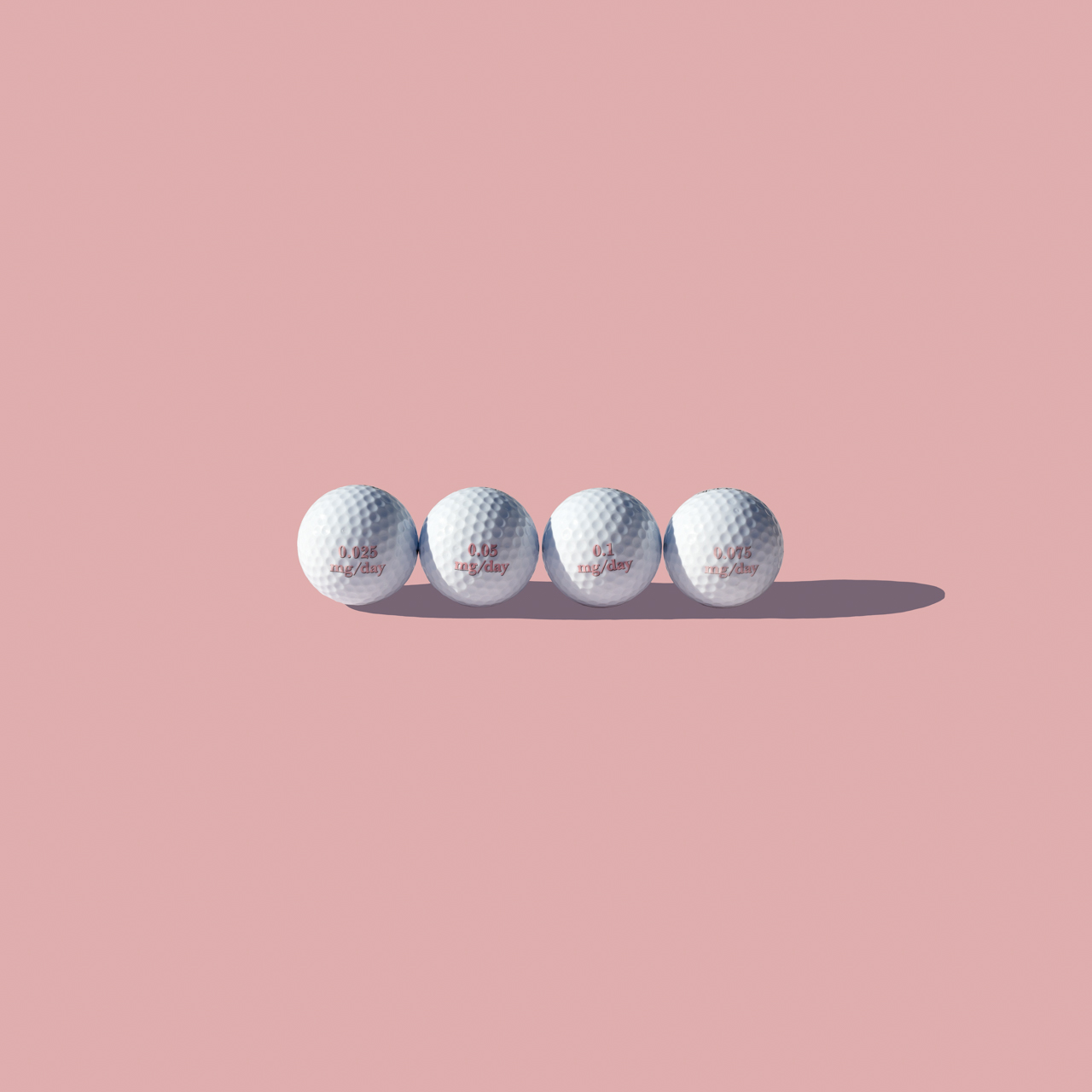

Big Pharma is a series of photographs of objects used for pharmaceutical marketing purposes. In the waiting room at a doctor’s office, I found myself suddenly aware of the branded objects around me. The clipboard and pen used to fill out paperwork, the clock on the wall, and the pamphlet holders on the table. Mimicking the style of pharmaceutical advertisements on television and cut from glossy magazines, I photographed these objects against colored backgrounds and fabric with patterns related to the medical industry, such as hospital gowns. By removing the medication name and the pharmaceutical company’s logo, I render the items anonymous. Only through the title does the viewer gain knowledge of its original purpose.

In 2008, the pharmaceutical industry began reducing the amount of branded items – golf balls, pens, mugs, stethoscope tags – given to doctors to encourage them to prescribe certain drugs. This reduction in branded items, however, did not result in a decrease in marketing spending. Today the U.S. spends over $30 billion a year, with 68% going towards marketing to medical professionals and the remainder on direct-to-consumer advertising. The United States and New Zealand are the only two countries that allow direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription drugs.

Big Pharma

Paxil, GlaxoSmithKline

Intal, Pfizer

Duragesic (Fentanyl), Johnson & Johnson

Ambien, Sanofi-Aventis

Tarka, Abbvie

Nasacort AQ, Sanofi-Aventis

Oxycontin, Purdue Pharma

Valium, Roche

Celebrex, Pfizer

Gabitril, Teva

Viagra, Pfizer

Celebrex, Pfizer

NovoLog (Insulin), Novo Nordisk

Unasyn, Pfizer

Wellbutrin SR, GlaxoSmithKline

Tylox (Oxycodone & Acetaminophen), Johnson & Johnson

Advair, GlaxoSmithKline

Effexor XR, Pfizer

Benicar, Daiichi Sankyo

Estradiol, Mayne Pharma

Adderall XR, Shire

Lozol, Rorer

Big Pharma is a series of photographs of objects used for pharmaceutical marketing purposes. In the waiting room at a doctor’s office, I found myself suddenly aware of the branded objects around me. The clipboard and pen used to fill out paperwork, the clock on the wall, and the pamphlet holders on the table. Mimicking the style of pharmaceutical advertisements on television and cut from glossy magazines, I photographed these objects against colored backgrounds and fabric with patterns related to the medical industry, such as hospital gowns. By removing the medication name and the pharmaceutical company’s logo, I render the items anonymous. Only through the title does the viewer gain knowledge of its original purpose.

In 2008, the pharmaceutical industry began reducing the amount of branded items – golf balls, pens, mugs, stethoscope tags – given to doctors to encourage them to prescribe certain drugs. This reduction in branded items, however, did not result in a decrease in marketing spending. Today the U.S. spends over $30 billion a year, with 68% going towards marketing to medical professionals and the remainder on direct-to-consumer advertising. The United States and New Zealand are the only two countries that allow direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription drugs.